How to Delight Kids & Teachers with a Creative Writing Workshop

School visits are one of the greatest joys and stresses of being a children’s book author. It’s exciting to meet the kids who love and inspire your stories, but creating an engaging visit can be a challenge.

In today’s article, author Mina Witteman shares one of her most successful workshops for school visits. Learn how she encourages and captivates middle-grade students through teaching them story writing basics. Design your own school visits inspired by this peek into Mina’s workshop.

The Dance to a Book

After seven middle grade novels, a Little Golden book and some forty short stories, seeing my work in print still elates me and intimidates me. I’m elated because there is nothing more fulfilling than holding your book in your hands. Intimidated because it’s when the marketing dance starts. And my, that is a hard one to master! It makes the foxtrot seem like child’s play.

These days, mastering that dance seems essential for a book to succeed. Some of us are lucky to have publicists, others have guidance from their publishing houses, but most of us are on our own. I’d love to share one of my school visit formats with you.

Dancing into Schools

Most schools won’t assign more than 55 minutes for author visits. That is ample time to do a reading and a Q&A, but I enjoy a more active visit. Since I am also a certified teacher of creative writing, I combine my skills and offer writing classes for grades 4 and up.

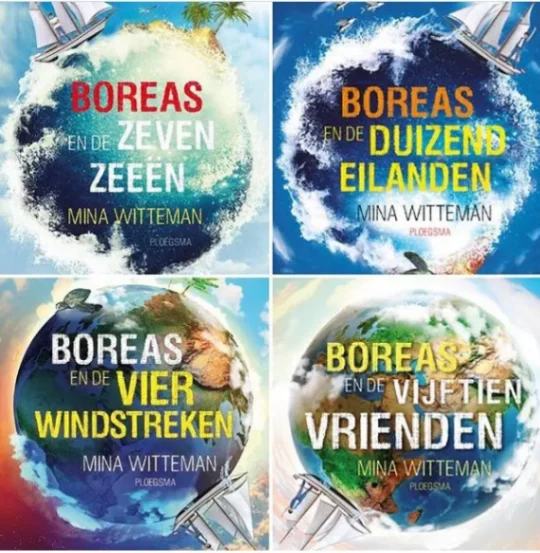

I designed this class for a middle grade audience and tie them to my book(s) or to themes in the book. I have a four-book adventurous middle grade series that touches on a myriad of topics, from refugees to plastic pollution to friendship to family to different cultures to modern-day pirates. Often, I also confer with teachers about their needs and wishes with regard to the school’s curriculum.

The Steps

Once I have a theme, I anchor it in my workshop. The design is always the same, though I make sure I can easily vary it in length by adding or leaving out steps, and by shortening or lengthening the time for each step. All the children need is a few sheets of paper and a pencil.

Step 1: Introduction – 5 to 10 minutes

After a brief introduction of myself and my books, I read a scene from the book that ties into the workshop’s theme. I always try to find a scene that has both the theme and, in whatever way, a personal memory woven into it. I use that personal memory to show that writers often use personal memories in their novels, be it the actual experience (a scene’s action) or the emotion of a memory. Using personal experiences will make it easier for the children to kickstart their story. I also explain that writing stories takes time, that we will only get to draft our story. They can finish it in their own time.

Step 2: Protagonist – 5 to 10 minutes

The children divide the paper into two columns, one titled GOOD, the other NOT SO GOOD. I explain that interesting characters are never perfect: they have good traits (patient, timely, helpful) and not so good traits (impatience, sloppy, quick to quit). I always assure them that a less good trait can sometimes come in very handy, like with my protagonist Boreas who is impetuous, but because of that, he rescues a refugee from drowning. The children write down three in each column.

Step 3: Conflict – 5 to 10 minutes

After a short introduction of conflict (problem) and why every story needs one, I ask them about Little Red Riding Hood and what her problem is (the wolf!). What happens when we take the wolf out of the story? Right… boring! The children, alone or in groups of four, think up four new problems for Little Red Riding Hood: a tiny problem, a slightly bigger problem, a huge problem, and a catastrophic problem. Then I ask two or three children or groups to share these new problems with the class.

Step 4: Show Don’t Tell – 5 to 10 minutes

To demonstrate this idea, I write down the sentence: Anna was scared. Then, I invite a few children to show how being scared looks like. What is he/she doing? Look at his/her face. The children write down a quick description of Anna without mentioning the word ‘scared’, no more than one sentence. I invite a few children to read their sentence, and we discuss which ones work best.

Step 5: Senses – 5 to 10 minutes

Name the five senses. Let the children think of a place for their story and describe it in no more than five sentences, using three senses. I ask a few children to read aloud, and we briefly discuss the senses used.

Step 6: The Four-Paragraph Story – remaining time

This is where the real work starts. I ask the children to divide a blank page horizontally in two and again in two, so they’ll end up with four parts. I give one assignment per paragraph and assure the children that it’s okay if they haven’t finished the assignment before we move on to the next paragraph. It’s a draft, and they’ll have plenty of time to finish the story later.

Here are the paragraph instructions:

Paragraph 1: In this first part, they’ll write something about the place where their story is set. I remind them to use some of the five senses. At the end of this part, they introduce their protagonist.

Paragraph 2: Something happens that disrupts the peace of the first paragraph. A problem arises. The protagonist runs into someone, finds something, or sees something. I remind them of Little Red Riding Hood’s problems.

Paragraph 3: A new, possibly scary situation arises. The protagonist searches for solutions, alone or with others, to restore the peace. I remind the children that characters have good and not so good traits. Does the protagonist have a trait that he or she can use to solve the problem?

Paragraph 4: Describe how the protagonist solves the problem. Try to round up the story by, for instance, ending at the same place the story started. The protagonist has changed because of what happened, he or she is wiser, has gained insight, made new friends.

I end the class by encouraging the children to finish and perfect the story at a later date, urging them to make it no longer than a page and a half. They can smooth out paragraph transitions, correct spelling and grammar, add illustrations, and, finally, read each other’s stories for feedback.

One of the greatest joys of these school visits is when the teacher, once the children have their final versions written and illustrated, bundles the stories into a book and sends me copy. Over the years, I have collected an impressive library of these anthologies and I always take a few with me to a school visit. Even the most reluctant reader/writer finds inspiration in these enchanting examples.

Mina Witteman writes in English and in Dutch. She has published a Little Golden Book, seven middle grade novels, and over forty short stories in the Netherlands. The Boreas series tells the story of twelve-year-old Boreas, who circumnavigates the world with his parents on a sailboat. The series, of which the fourth book just came out, is lauded by readers, teachers and librarians alike.

Mina teaches creative writing and mentors published and pre-published writers. She is an active volunteer for the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators in the United States and Europe and currently holds the position of International Published Authors’ Coordinator. She is the Program Associate for Children and Young Adult for the Bay Area Book Festival. Mina lives in Berkeley, California.

Check out just a few of Mina’s books: El Nido de Mia (Spanish) and Boreas en de Vijftien Vrienden (Dutch). Find her on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and her website.

%20(1)_1718912244625.png?alt=media&token=ff7e6e75-c524-41cd-9202-fb41b2ac69be)